Central Annamitic Range where the Woodsman has been spotted

The mountain people of the Indochinese peninsula are imbued with the supernatural, with tales of evil spirits, terrestrial powers, and woodland, water or mineral creatures embodying a timeless expression of collective fears. Myths and superstitions often manifest themselves in the form of anthropomorphic deities, such as Lissu ogresses, Hmong werewolves, Silla tiger-women, Jarai forest girls, Raglai flower-women, or Maa’ river nymphs. Despite the disappearance of the great forest, one myth persists: the Nguoi Rung, or the Woodsman. The enduring power of this myth, the fear it elicits, the tales told by colonial explorers and ethnographers, and Secret Indochina’s exploration of the South Vietnam massif provide an opportunity to explore the persistence of ancient fears, how myths are passed down through generations, and the line between myth and reality in the proto-Indochinese imagination.

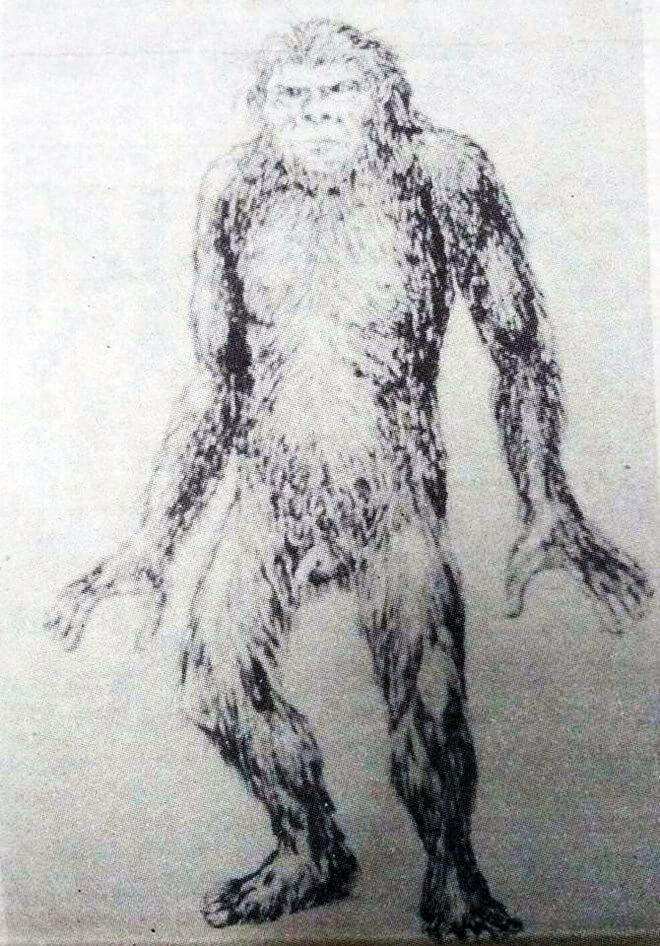

Representation of a Vietnam Woodsman - Nguoi Rung

To understand the myth of the Woodsman, it is necessary to understand the natural environment that spawned it and the disastrous consequences of recent decades. In ancient times, the highlands were heavily forested, with intertwining massifs, hilly plateaus, and semi-arid bushes that stretched across central Vietnam, south Laos and eastern Cambodia. The country was ruled by about 40 Austronesian or Austro-Asian groups and sub-groups who were often hostile to foreign presence. They were fierce people of the forest who lived at the mercy of nature, slash-and-burn practices, monsoons, ethnic conflicts, and clan fights. It was a hard world shaped by grandiose nature, a hellish country in a dream setting. Its people lived in perpetual fear of the great forest, a mysterious world that was home to evil powers or woodland creatures. While the myth of the Woodsman was strongest in the densely forested southern highlands, tales of similar creatures such as the Yeti and Bigfoot extend beyond Vietnam to Bhutan, Southeast Asia, Central Europe and North America.

In Vietnam, the existence of the Nguoi Rung was first reported by travelers in the central plateau, including the explorer Henri Maitre, the administrator Jules Harrois, and Jacques Dournes, missionary and ethnographer of the Foreign Missions and specialist on the Jaraïs and Coho (Sre) peoples. Dournes’ approach to Jarai forest myths is unique and precise; he collected lists of fabulous creatures, explored the line between imagination and reality where woodland creatures depart from known zoological species and merge into the improbable. According to Jarai oral myths, their forests concealed various varieties of Woodsmen. Some were purely illusory, such as the Klöng, a cannibal who captured small children to lure crocodiles; the Kang, a kind of pygmy; and the fearsome Nah Tan with its swords instead of arms. The Kömri comes closest to the common description of the Woodsman: tall, fast, living in deep forests, and covered with a reddish-brown coat. Dournes also drew a strange connection between the orangutan and the Raglai people, since the word “orangutan” is similar to the South Vietnamese Austronesian term Orang Glai (literally, ape-men, forest men), which is the ancient terminology for the Raglai.

-1578375077.jpg)

The Woodsman forest

In the 1920s, Commander Baudesson also reported creatures in Phu Yen:

“The forests of Phu Yen were haunted by these monsters, human hunters. Having captured them, he brought them back to his cave, waiting for night to perform incantations and hysterical rites, his hands raised to the heavens. In order to escape such an unfortunate encounter, when they were forced to cross the regions where the monster lived, the locals surrounded their arms with large bamboo tubes. Thus, if they were apprehended by the thing, they would leave these armbands in the hands of the aggressor when he engaged in his ritual rites and fled.”

Woodsman Cave

Woodsman Cave

During the Vietnam War, many battles were fought in the jungle. There were American testimonies about the Woodsman creature, but they were excessively fanciful. Reports from Vietnamese fighters were more credible, since the Viet Cong hid, fought and lived for years in the darkest corners of the forests. Minh Ngoc Van, a former soldier, refers to North Vietnamese Army troops that were more terrorized by inhuman screams than the whistling of shells.

Shell from Woodsman Cave

In his book The Sorrow of War, the Vietnamese writer Bao Ninh recounts these disturbing facts: “One day, Thinh the Chief, of the first company, ventured into the ashes of the village, killing a huge gorilla. They started to transport the animal to the scout camp in foursome. They laid him down on the ground, they began to shave the beast's hair. They then saw a plump woman appear, with peeled skin, half grey, half white, with repulsed eyes. Aghast, Kien and the whole gang shouted, and fled, leaving pots and cutting boards behind. No one in the regiment believed that story. Yet it was true. They had buried this person in a decent grave. But they couldn't avoid his revenge. Shortly afterwards, Thinh the Chief was killed.”

In 1974, General Hoang Minh Thao, Commander of the Highland Forces, established the 5202 program headed by Professor Vo Quy to collect oral myths. Professor Tran Hong Viet discovered various clues including an imprint, but the research was abandoned in 1990 for lack of resources. In the 1990s, the Australian professor Helmut Loofs-Wissowa, a student of the founder of cryptozoology B. Heuvelmans, visited Central Laos in search of the Woodsman. Accompanied by a Japanese TV team, he gathered various testimonies and posited that the Woodsman was a remnant of a forgotten Neanderthal branch. In the last decade, Secret Indochina organized an expedition in a South Vietnam Raglai massif and collected various mysterious accounts.

Woodsman ravin survey

Today, the Vietnam Woodsman remains as mysterious as ever. Studies have been abandoned, the great forest is retreating, forest myths are dissipating, and the collective memory is being extinguished. But the myth still lingers in the mountain sanctuary of the proto-Indochinese, the last bastion of a fleeting world